Background

Applications of two-phase fluid cooling are broad and ubiquitous. From refrigerators, air conditioners and dehumidifiers, to nuclear power plants, data centers, and space exploration, engineers takes advantage of the high heat transport capability of the vaporization phenomenon in two-phase fluid to efficiently cool down important systems in our lives. That is, heat is more efficiently removed by a fluid that is vaporizing through boiling, than simply liquid (i.e. subcooled). Subcooled liquid is liquid at a temperature (and pressure) below the saturation (normally referred to as the “boiling”) temperature (and pressure).

Two-phase flow regimes

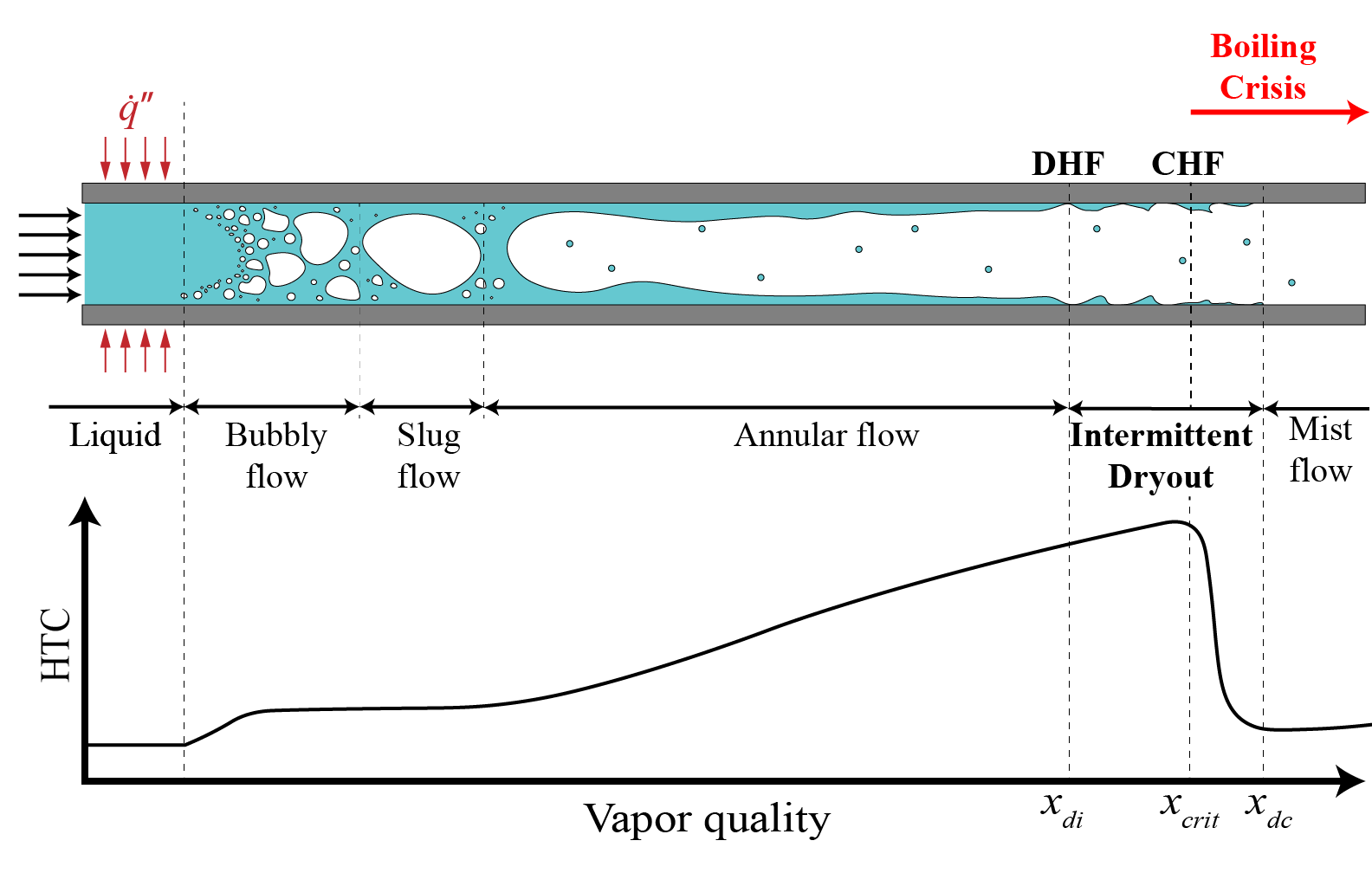

Moreover, different boiling regimes (i.e. types) offer different heat-transfer capabilities. Figure 1 below shows the different regimes of boiling as a subcooled liquid flows through a heated (q” represents the heat flux) pipe. The lower chart in the figure shows the heat-transfer coefficient (HTC, units: [W/m^2-K]) of the flow in each flow regime. If the most efficient flow is one that can remove the most heat (Joules of energy) in a given time (i.e. watts of power) within a certain surface area (say, of the pipe), at a given pipe wall temperature, the figure suggests that it occurs during the annular flow & intermittent dryout regimes.

We want to operate cooling systems in this high-HTC regime, but our lack of understanding and control in the underlying physical (mass and energy transport) phenomenon forces critical systems to operate in the subcooled to the bubbly flow regime. We are unable to predict with sufficient confidence when the flow regimes passes intermittent dryout and enters a boiling crisis in the mist flow regime, where the HTC drops precipitously. Unlocking the potential heat-transfer capabilities of such a two-phase system by gaining better insight on predicting the flow conditions to prevent a boiling crisis is one of the current approaches for developing higher-performance cooling systems.

Glossary

Annular flow: A two-phase flow regime where a saturated liquid annulus surrounds a saturated vapor core.

Dry out: The complete vaporization of liquid (usually described as a thin film) on a surface.

HTC: Heat transfer coefficient, the amount of energy transport associated with a fluid flow.

Vapor quality: the ratio of vapor in a bulk mixture of liquid and vapor phase fluids. The term originates from steam power generation. Since liquid droplets are undesirable in steam machineries, a high quality steam is a steam with mostly vapor.

What about annular and intermittent-dryout flows?

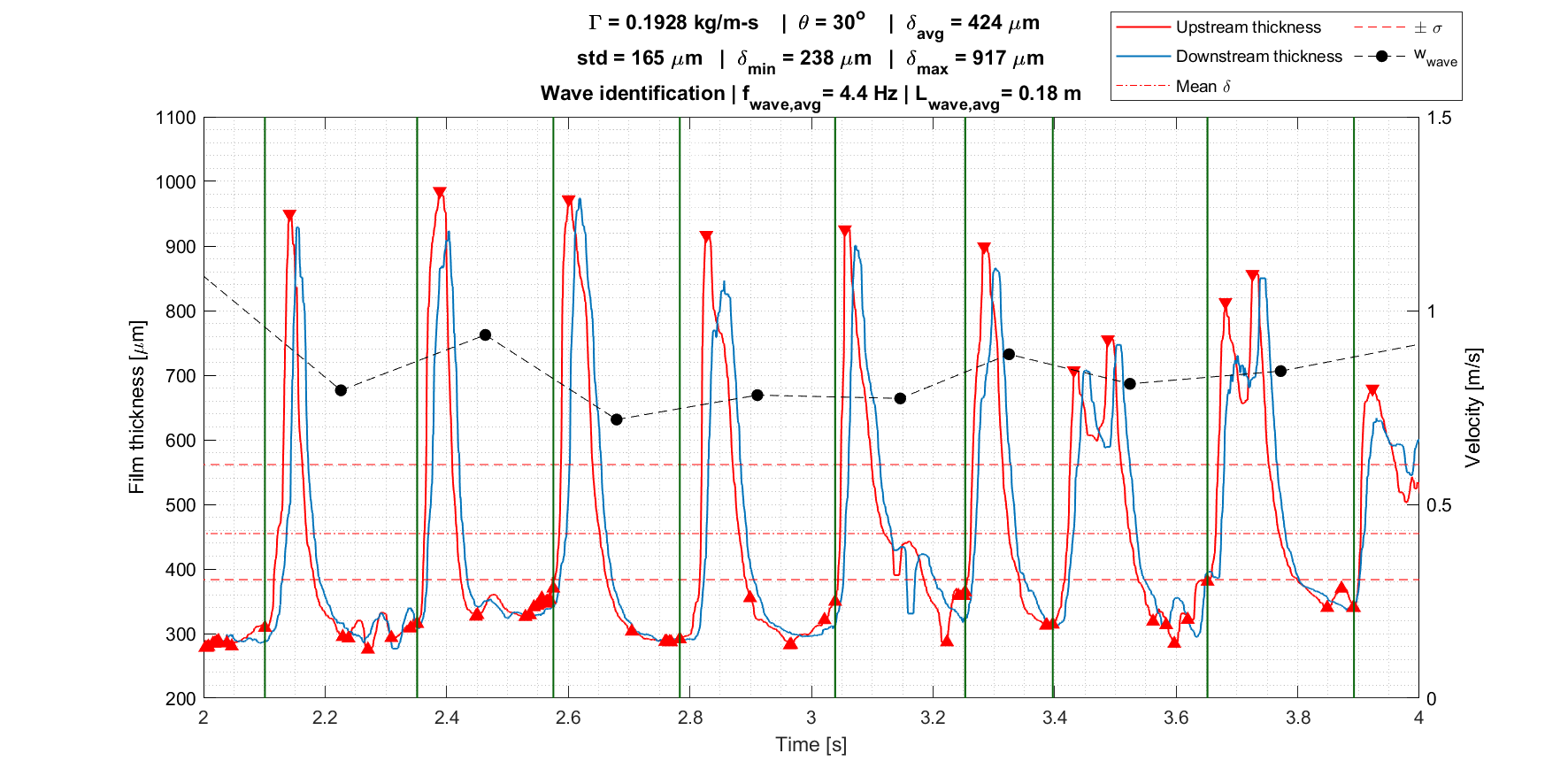

There are many proposed methods in which the annular and intermittent-dryout flow regimes have an increasing HTC compared to the lower vapor quality flows. One method is the occurrence of disturbance liquid waves in these flow regimes. The disturbance waves exhibit higher stream-wise velocity than the average liquid base film thickness, and increase in thickness compared to the average liquid film. In a heated annular flow, as more heat is transferred to the liquid annulus, liquid is evaporated into the vapor core, thinning the liquid film. The disturbance waves that occur naturally replenish the thinning film, avoiding a complete dryout on the heated pipe surface. This can be seen in Video 1, below.

Video 1. A disturbance wave front rewets the dried-out portion of the wall, where all the thin liquid film had vaporized.

Research focus

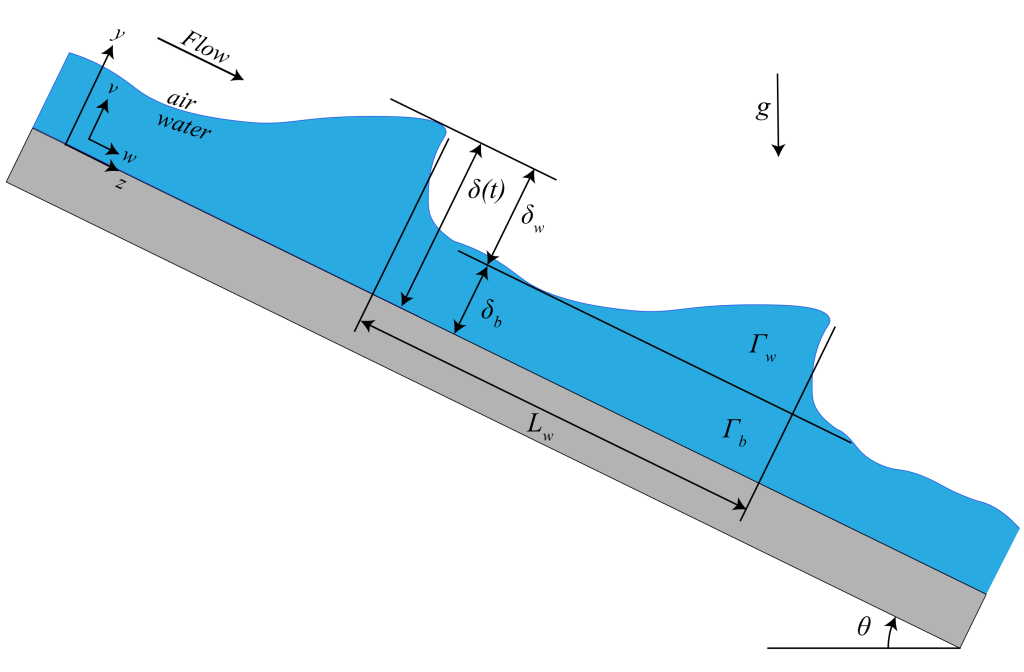

The focus of my research is to identify the variables that affect disturbance wave characteristics. Wave characteristics refer to variables such as wave height, velocity, shape, frequency, intermittency, etc. Since annular flow occurs under saturated (“boiling”) conditions, and is inherently turbulent, chaotic, and more difficult to control precisely, an alternative experimental setup using air as vapor and water as the liquid in a falling film was used.

Details of the experimental method are omitted for brevity. Two non-intrusive optical film thickness sensors are placed a set distance apart in a falling film, and a typical experimental data is shown in Figure 3. The goal of this project is to understand how dynamic mode decomposition (DMD) and the Koopman operator can be used to provide insight to modelling the dynamic system of disturbance waves in falling films.

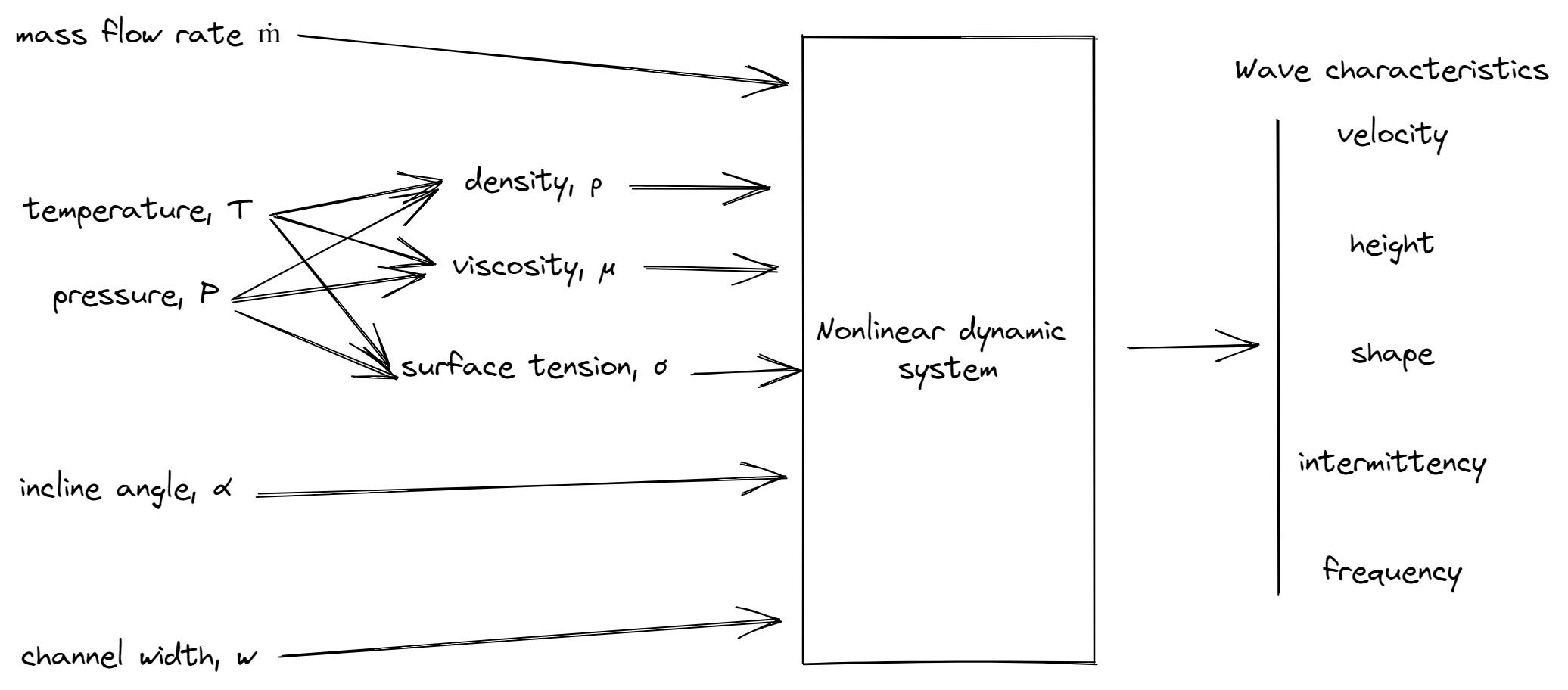

While DMD doesn’t exactly fit in the frameworks mentioned in class currently, there are a series of random variables that can be considered. First, all the wave characteristics can be “effect” random variables. Second, the variables that can be easily manipulated are mass flow rate and incline angle. In the falling film version of disturbance waves, gravity is the main force creating flow. The angle in which the flow is set at affects the gravitational acceleration on the liquid in the direction of the flow channel. Finally, intensive fluid properties (density, viscosity, surface tension, etc) are all intervened variables as only water is considered in this experiment. The fluid temperature and pressure are also intervened properties. They affect fluid properties, but are effectively held constant. Directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) may not be the most effective method of describing the dynamic process. They can, however, help understand what variables are involved, as shown in Figure 4.

Moving forward

In the spirit of working on a project that helps my research, this project will be different than most. It will involve me learning about DMDs and the Koopman operator/matrix/algorithm/method independently. If feasible, I will then attempt to apply the method on some of my existing data, and report the results. If it is not feasible, I intend to still report my findings. The papers on this subject tend to get dense and out-of-hand quickly. I’m currently watching Prof. Nathan Kutz‘s videos to learn more about the methods.